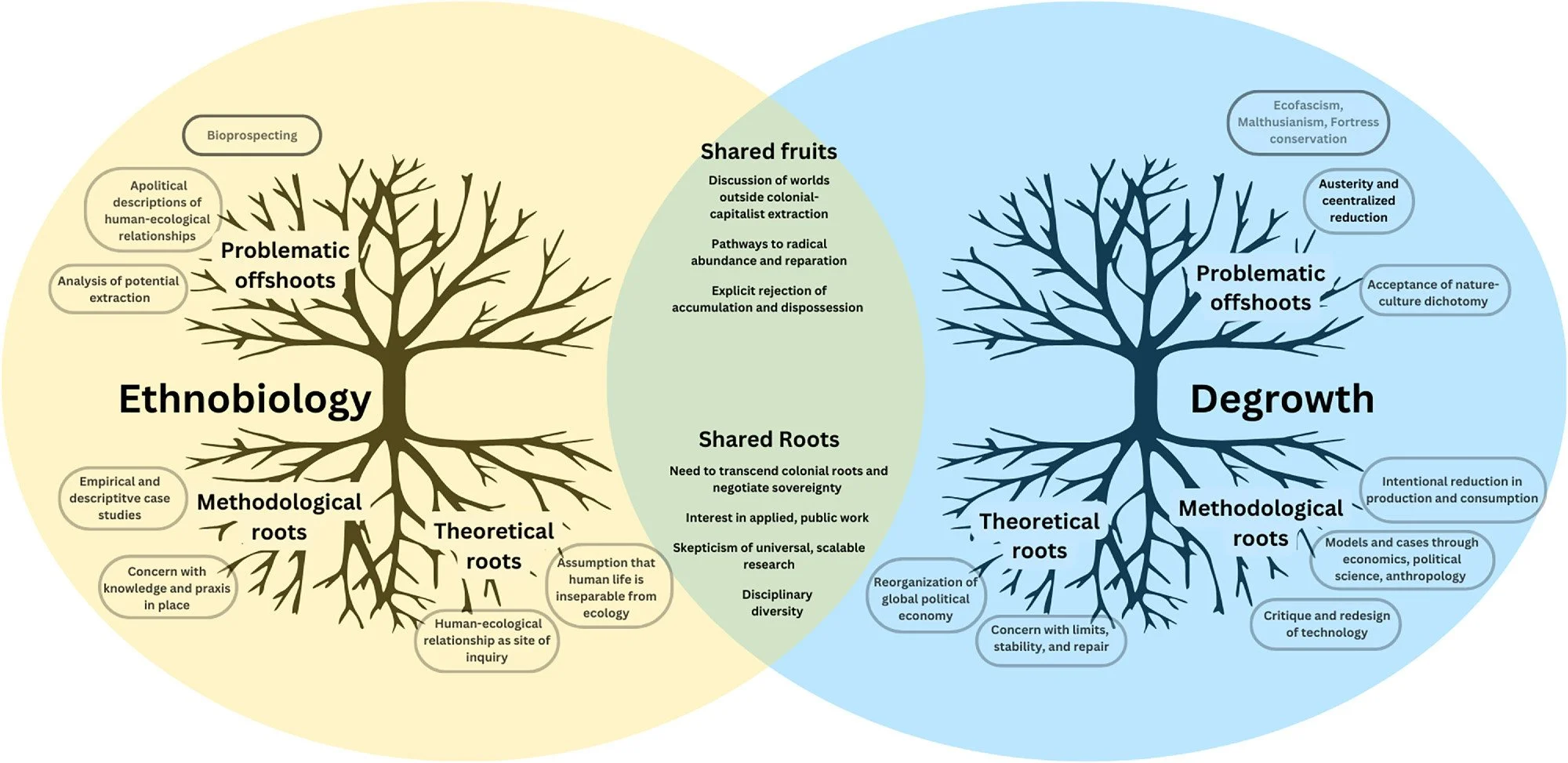

Ethnobiology offers meticulous case studies into the web of life, neither studying life apart from human influence nor centering its intersection with humans. While we work in a world shaped through colonial hierarchies and capitalist extraction, we rarely center this context in our research. Degrowth research offers a vocabulary to contribute to larger discussions of political economy and political ecology. It tends to emphasize political economy and industrial relations, centering/combatting capitalism while glossing the fine details of how communities co-create environments.Both conversations work to transcend problematic histories: ethnobiology opposes extraction and appropriation, while degrowthers reject Malthusian and ecofascism. But as long as these inform public conversations around human–ecological relationships and downscaling, the work is never finished.If the point of our work is not just to interpret the world in various ways but to change it, then ethnobiology and degrowth scholars are allies in action-oriented, imaginative research. Both ask how to scale up reciprocity and care. This is a way of being, a relationship. It is not a product.

Flachs, Andrew and Ashley Glenn. 2025. “We are just surviving:” The paradox of robust homegardens in Northern Bosnia and Herzegovina. East European Politics and Societies. 39(4): 1001-1018. https://doi.org/10.1177/08883254251394653.

Flachs, Andrew. 2025. “Ethnobiology and Degrowth.” Journal of Ethnobiology. https://doi.org/10.1177/02780771251374886

Flachs, Andrew. 2022. “Degrowing alternative agriculture: institutions and aspirations as sustainability metrics for small farmers in Bosnia and India.” Sustainability Science. 17(1):2301-2314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-022-01160-9.

Flachs, Andrew and Glenn Davis Stone. 2019. “Farmer Knowledge Across the Commodification Spectrum in Telangana, India.” Journal of Agrarian Change, 19(4):614-634.